History of Old Fort Ripley

1848-1877

By Jack K. Johnson

November 2015

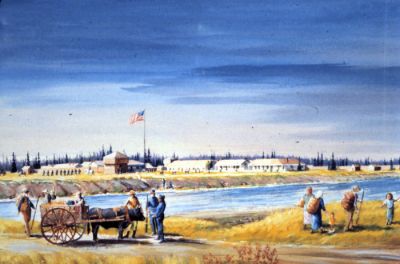

Fort Ripley was a nineteenth century army outpost located on the upper Mississippi River in north central Minnesota. It was on the very edge of the nation’s northwestern frontier when it was built, providing a government presence in the wilderness and bolstering settlement. Like most frontier army posts during that era, it was geographically remote, on a navigable river and an important supply route, and American Indians lived nearby.

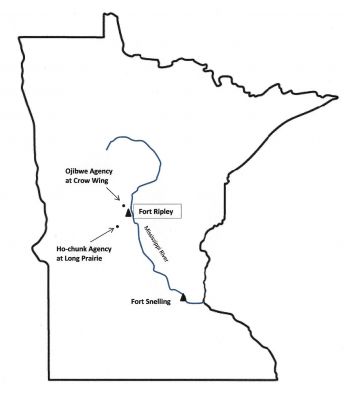

The decision to locate and build Fort Ripley was driven by an 1846 treaty that removed the Ho-chunk (Winnebago) Indians from their lands in northeastern Iowa to a new reservation near Long Prairie. The treaty specified that a military post be established nearby. The chosen site for the new fort also put it in proximity with the trading post and growing settlement of Crow Wing, seven miles upriver at the confluence of the Mississippi and Crow Wing Rivers. The “Woods” ox-cart and wagon trail, which carried fur and supplies between Fort Snelling and Fort Garry (Winnipeg), crossed over the Mississippi at Crow Wing, and Crow Wing was home to the Ojibwe Agency, located a few miles outside of town. The government hoped the Ho-chunk, and the fort, would serve as a buffer between the warring Eastern Dakota (Sioux) and Ojibwe (Chippewa) tribes.

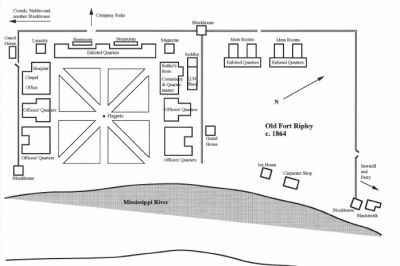

Construction began in November 1848 on the west side of the Mississippi, opposite the pioneer farm of Baldwin Olmstead, who provided supplies for the soldiers. The buildings were wooden and lined up along three sides of a square open to the river. Four raised blockhouses offered tactical vantage points. A ferry was built to transport men and goods across the river because the Mississippi was not navigable north of St. Cloud and supplies had to be brought north using the wagon trail, which ran along the river’s east side. The new post was initially named Fort Marcy, was renamed Fort Gaines the following year, and finally in 1850 named in honor of Brigadier General Eleazar W. Ripley, a Maine congressman who had distinguished himself in the War of 1812.

On April 13, 1849, the post's first garrison—Company A, 6th U.S. Infantry, consisting of two officers, four sergeants, three corporals, and 39 privates—arrived from Fort Snelling under the command of Captain John B. Todd. The post was built to accommodate two companies but, except for 1862-65, never housed more than one.

Life at Fort Ripley was usually uneventful. The isolation, summer mosquitoes, and long, cold winters challenged everyone at the garrison. Twice each year, the soldiers marched to the Long Prairie Agency to supervise government annuity payments of money and goods to the Ho-chunk, and then did the same for the Ojibwe at their Agency in Crow Wing.

The Ho-chunk reservation was poorly situated, and in 1855 the discontented tribe was moved yet again—this time to a more hospitable location in Blue Earth County in south-central Minnesota. Thinking the post was no longer needed, the army decided to close Fort Ripley. The garrison was withdrawn in July of 1857, but almost immediately, lawlessness broke out among whites and Ojibwe alike, causing the army to reactivate the fort in September.

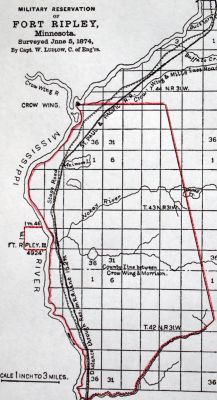

As was common for frontier posts, Fort Ripley was initially located on a large military reservation. These reserves were vast tracts of land intended to prevent incoming settlers from encroaching upon the fort itself, and to provide ample acreage for gardens, forage, and lumber needed by the garrison. Because of their size, the reserves were a constant source of friction between the army and squatters and homesteaders who wanted the military lands opened for settlement.

In the case of Fort Ripley, the initial reserve was huge. Located on the east side of the Mississippi River, it consisted of nearly ninety square miles (over 57,000 acres), with a single square mile (1000 acres) set aside for the fort itself on the west side of the river. After much agitation, the army agreed in 1857 to sell its east side lands in public auction, but local settlers, by mutual pact, underbid the property. The Secretary of War later annulled the sale because the bids were so low, but in the meantime, settlers established homes and farms on the land. The resulting confusion and litigation took twenty years to untangle.

Upon outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, the army regulars were withdrawn and sent south to fight Confederates. For the remainder of the war, various companies from Minnesota’s volunteer regiments manned Fort Ripley.

Trouble came in August 1862 when Dakota Indians under chief Little Crow began fierce attacks against white settlers in southern Minnesota. Seizing upon the moment as an opportunity to gain power and leverage for redress of grievances, Ojibwe chief Bagone-giizhig (Hole-in-the-Day II), who lived in Crow Wing, threatened to launch a simultaneous war against whites in northern Minnesota. Prisoners were taken and several buildings in the area were destroyed. It was rumored that Bagone-giizhig and Little Crow had entered into a pact. Fearful settlers flocked to Fort Ripley for protection. Additional soldiers were rushed in and the post was readied for battle.

Fortunately, the threat was defused in September, thanks in part to the garrison’s strengthened defenses. For the next three years, on the heels of the U.S.-Dakota War, Fort Ripley became a headquarters, supply base, and staging area for military campaigns that extended as far west as the Yellowstone River. Activity reached its peak during the winter of 1863-64, when nearly 400 troops and 500 horses were quartered at the fort. Army regulars returned to garrison the fort in 1866.

By the mid-1870s, the frontier was 500 miles to the west. The village of Crow Wing was becoming a ghost town because the railroad had decided in 1871 to run through Brainerd rather than Crow Wing, and because most of the nearby Ojibwe had moved to a new reservation set aside for them at White Earth.

On a sub-zero night in January 1877, an overheated chimney started a fire that consumed three buildings by morning, including the main storehouse. No longer in the wilderness, nor troubled by nearby Indians, the War Department decided to close the post permanently rather than rebuild. In July the flag was lowered for the last time and the garrison moved out.

The buildings stood abandoned until the early 1900s, when local farmers began “harvesting” salvageable lumber and bricks. The ruins of the powder magazine, the post's only stone structure, are all that remain today of this pioneer fort.

When it was decided in 1929 to build a new training site in central Minnesota for the National Guard, the remains of old Fort Ripley were, purely by coincidence, within the proposed boundaries. The new post—Camp Ripley—took its name from the old.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Baker, Robert Orr. The Muster Roll – A Biography of Fort Ripley Minnesota. St. Paul: H.M.Smyth, 1972.

Diedrich, Mark. "Chief Hole-in-the-Day and the 1862 Chippewa Disturbance: A Reappraisal." Minnesota History, Spring 1987: 193–203. Viewable online at http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/50/v50i05p193-203.pdf

Field, Ron. Forts of the American Frontier: 1820-91: Central and Northern Plains. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2005.

Folwell, William Watt. A History of Minnesota Vol. II, 374-382. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1924. Viewable online at https://archive.org/stream/historyofminneso02folw#page/n7/mode/2up

Prucha, F. Paul. “Fort Ripley: The Post and the Military Reservation.” Minnesota History, September 1947, 205-224. Viewable online at http://www.mnhs.org/market/mhspress/minnesotahistory/xml/v28i03.xml

Prucha, Francis Paul. Military Post of the United States, 1789-1895. Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1964. (2nd printing in 1966 includes corrections)

Rickey, Don Jr. Forty Miles a Day on Beans and Hay. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963.

Treuer, Anton. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul: Borealis Books, 2011.